Shear wave elastography – reducing need for invasive biopsy

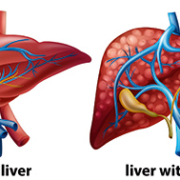

Liver disease is a growing problem across the world. It includes a large range of disorders, such as fatty liver disease (both alcoholic and non-alcoholic), drug-induced liver damage, primary biliary cirrhosis and hepatitis (viral and autoimmune).

Biopsy is gold standard for liver disease

Fibrosis is a relatively common consequence of chronic liver diseases, and its staging, alongside exclusion or confirmation of early compensated cirrhosis, are considered to be vital for surveillance and treatment decisions.

The gold standard for the confirmation of hepatic fibrosis is biopsy. However, biopsy of the liver has several disadvantages. First of all, it is invasive. It is also associated with rare but serious complications. Finally, it can sample only a small portion of the parenchyma (functional rather than connective tissue). This makes it vulnerable to sampling errors.

Non-invasive tests becoming norm

To overcome such constraints, a variety of non-invasive imaging and serological methodologies have been researched and developed for assessing fibrosis. Aside from staging, an ever-growing corpus of data from non-invasive liver tests is also yielding considerable insights for prognostic patient care.

Liver biopsy is now largely restricted to patients showing unexplained discordances in non-invasive testing or those where hepatologists suspect additional etiologies of the disease.

Indeed, non-invasive tests are fast becoming the norm in much of the world, outside the US, although there are several exceptions. The reasons for the lower penetration of non-invasive tests in the US are discussed later.

Ultrasound at forefront

New non-invasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis consists of ultrasound elastography, a diagnostic methodology to evaluate stiffness of tissue, magnetic resonance elastography and serologic testing.

To some of its proponents, elastography is simply a form of the centuries-old systems of diagnosing and assessing diseases via palpation, now extending beyond the scope of physical touch.

While a biopsy is invasive and carries bleeding and infection risks, elastography is seen as a way to get the data needed by clinicians to diagnose and stage liver diseases without the associated complications.

Ultrasound-based elastography is not only used as an alternative to liver biopsy for measuring fibrosis, but also to predict complications in patients with cirrhosis. Another advantage is that elastography, like other non-invasive imaging modalities, can be repeated as often as required to monitor disease progression. Due to their risks, this is simply not feasible with biopsy.

Strain elastography and shear wave elastography

The best-known commercial ultrasound-based techniques for assessing fibrosis include strain elastography and shear wave elastography (SWE). SWE is a real-time two-dimensional elastography technique which enables making quantitative estimates of tissue stiffness in kilopascals (kPa) by virtue of the shear wave speed.

Technologically, even though strain elastography predates SWE, the latter is more easily reproducible than strain elastography, and has rapidly gained interest as the preferred technique. The two are quite different, and outside the hepatology area, seem to have significant complementarities.

Broadly speaking, strain imaging is a qualitative/semi-quantitative method influenced by histotype and lesion size. The use of semi-quantitative indices does not improve performance. Neither does it reduce interoperator variability.

SWE provides accuracy, comparability

Shear wave, on the other hand, is a quantitative method which provides a more accurate and easily comparable assessment of spatial distribution of tissue stiffness.

Most practitioners see SWE as quick and easy to perform, and easily repeated to monitor liver disease progression and measure the effect of a particular treatment. An ultrasound shear wave propagates like ripples of water, as it spreads across tissue. A coherent pattern indicates that a pulse has been applied properly and that there are no artifacts (e.g. from vessels) that would provide erroneous results.

SWE systems provide variable depth of measurement. A depth of 5-6 cms may make it difficult to scan the liver in a large or obese patient, but depths of up to 8 cms are available in certain SWE systems. However, results are not reproducible at such depths, across commercial SWE vendors.

Ease of use not universally accepted

Nevertheless, not everyone agrees that the procedure is easy, especially if SWE results need to be matched against reproducible serological tests. The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound notes the considerable training required for precision. SWE begins with the positioning of a patient in a left posterior oblique position with the arm raised. Patients need to also breathe slowly, and when asked, suspend breathing, since movement of the liver can reduce accuracy in measurement.

Liver is principal application for SWE

So far, SWE has been used to evaluate and quantify liver fibrosis/cirrhosis of multiple etiologies or with complicating co-morbidities, including chronic hepatitis, liver cancer, steatohepatitis, and biliary atresia. The two-dimensional shear wave elastographic technique offers better performance for assessing liver fibrosis as compared to conventional transient elastography, according to a May 2016 study in the Chinese publication, World Journal of Gastroenterology’.

SWE and hepatitis C

SWE practitioners see it as a tool to assist in earlier detection of conditions such as hepatitis C, and both fatty liver and alcoholic liver disease. Alongside lab studies, SWE offers a means to closely monitor the impact of treatment and assess if the liver will normalize. For many hepatologists, fighting a liver condition before Stage 4 cirrhosis provides a good chance of reversibility.

SWE can also provide information on which hepatitis C patients might benefit from viral therapy. There are numerous reports of patients who would not have been suspected of severe fibrosis or cirrhosis, based on traditional ultrasound grey scaling. At best, the latter provides indicators such as anomalies in the liver contour. However, it does not show signs of cirrhosis such as surface nodularity which are immediately apparent in elastography.

Guiding biopsies

Some clinicians have sought to use SWE to guide liver biopsies and in certain cases, avoid or postpone biopsy. As part of this process, they have addressed one of the major limitations of biopsy, namely restrictions to choice of affected areas, erroneous samples, or inadequacy in sample size enough for interpretation. SWE allows multiple sampling across the liver and generating a mean value. This reduces what in the past would have been a large number of unnecessary biopsies, and minimizes the morbidity of liver biopsy.

SWE in children

SWE has shown specific advantages in pediatric patients. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center is gathering data on normal’ stiffness values in children, and on rates of progression, given that published data is almost wholly based on adults.

The study groups cover children with liver transplants, metabolic disorders, cystic fibrosis and those on prolonged intravenous feeding (TPN). One specific area for attention is biliary atresia, a rare but life-threatening condition where the bile ducts in an infant’s liver lack normal openings. The bile builds up and causes damage to the liver.

The pediatric data collection for SWE on newborns with jaundice or cholestasis makes ten measurements. This adds just 5 minutes to a typical ultrasound exam.

Nevertheless, pediatric SWE also has its limitations. According to Dr. Sara O’Hara, who heads the Ultrasound Department at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, SWE can give variable results in areas such as children with non alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and fatty liver disease.

Breast applications benefit from SWE-plus-strain elastography

In adults, aside from the liver, SWE is seen as a useful technique for evaluation of breast lesions and prostate imaging. In both cases, the technique seems to provide best results in combination with another elastography mode.

For instance, a literature review published in the Journal of Ultrasound’ in 2012 reported that SWE and strain elastography complement each other and overcome mutual limitations in the evaluation of breast lesions.

Clearly, when both types of elastography provide similar results, there is a greater degree of confidence – especially in terms of a near-total elimination of false negatives, which sharply cuts the need for breast biopsies which later prove unnecessary.

There are however some limitations which have been reported in measuring shear wave velocity in the stiffest of breast lesions. Here, rather than propagating through the tumour, the shear wave tends to bounce back. Nevertheless, ongoing improvements in SWE, which have been further reducing examination time and enhancing field of view, means that at some point it could be a tool for breast cancer screening.

Prostate applications benefit from SWE-plus-MR elastography

The use of SWE in prostate cancer, too, shows similar potential for benefits as with breast screening. The first factor is a reduction in biopsies, which prove to have been unnecessary post facto. Studies are under way which seek to correlate stiffness with abnormalities (as well as aggressiveness of tumours) and to assist urologists determine when patients with low-grade prostate cancer must start treatment.

As with SWE and strain elastography in the breast, best results in terms of the prostate are obtained by complementing SWE with another imaging modality – magnetic resonance (MR) elastography. Some findings reveal SWE significantly superior in detecting prostate cancer in the peripheral zone – which is where most tumours occur. However, MR seems to show greater promise in the anterior gland and transitional zone.

Again, as with the breast, the fusion of two modalities permits multiple sampling and tackles a major limitation of prostate biopsy, namely inconvenience and risk, as well as limited choice of affected areas. A few experimental procedures have also targeted fusing MR and SWE images to help guide biopsies.

Using SWE in other organs

SWE has also demonstrated considerable (if still early-stage) promise for evaluating thyroid nodules, indeterminate lymph nodes and uterine fibroids. Another area for investigating SWE include kidney transplants, in order to to avoid excessive biopsies. However, limitations to shear wave captured depth remains a technology challenge for manufacturers to address.

US remains laggard in ultrasound elastography

While most of the world’s regions (Europe, Asia and Latin America) are seeing growth in the use of ultrasound elastography (both SWE and strain), in the US neither is eligible for reimbursement, even in the largest application area – the liver. This is unlike transient elastography, although critics allege it is a blind methodology which neither directly measure fibrosis and often over-estimates it.

Currently, studies in both the US and other parts of the world are seeking to establish the clinical and economic benefits of SWE and strain elastography, including unnecessary invasive biopsies with their associated costs and complications. Eventually, the results of ongoing trials are expected to produce the data which will make ultrasound elastography eligible for reimbursement.

The most self-evident advantage of ultrasound elastography is its non-invasive nature. Unlike a biopsy, it is clearly more feasible to use SWE to screen for patients at greatest risk of chronic liver disease and in need of referral or treatment.