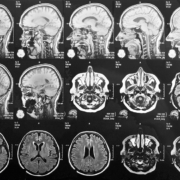

The frontiers of radiology – connecting patients

The march of healthcare technology is not always even. Benefits on one front can often be outweighed by problems on another. Radiology is no exception to this rule.

Like other medical professionals, radiologists have begun using portals and social media to connect to patients and join the move towards personal healthcare.

Websites and radiology

Today, websites staffed by imaging professionals seek to directly address the public about radiology. Such a trend is especially pronounced in the US. Examples include radiology Q&A portals at the University of Texas’ John P. and Kathrine G. McGovern Medical School, Northwest Radiology Consultants in Atlanta, Georgia, and a host of others. One of the best known is the RSNA/ACR public information website, RadiologyInfo.org, which offers a library of resources for patients including information on how various imaging procedures are performed. In Europe, the ESR has a Website page dedicated to ‘Radiation and Patients’ and an ‘Ask EuroSafe Imaging’ Q&A page, split into three sections (CT, interventional radiology and pediatric imaging), with answers provided by radiologists from across the continent.

Radiologists and social media

Radiologists have also sought to use social media to build and continuously strengthen interactive relationships with patients outside a formal hospital or physician office setting. Such approaches have spilt over into tackling concerns after widespread reports in the media about the ‘over-use’ of medical radiation. In the US, for example, the Health Physics Society has a site dedicated largely to addressing such risk perceptions in the general public. The UK too has seen such a step with the British Institute of Radiology and the Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine endorsing Ask for Evidence, as part of which a panel of radiologists and medical physicists respond to questions from the public on radiation safety.

Technology versus patient downtime

These are clearly significant and laudable developments. Informed patients are increasingly regarded to be better patients by several physicians. However, other recent developments in technology, above all electronic medical/health records (EMR/EHR), are placing a growing burden on clinicians to update medical documentation, in order to facilitate real-time sharing and reduce errors. This results in less time for patient care. A key driver here, in the US, consists of federal government meaningful use (MU) requirements, which provides physicians with financial incentives to use EHRs.

For radiologists, these incentives are hardly negligible and range from 44,000 to 63,750 dollars (39,000 to 56,735 Euros) over a 5-or 6-year period via Medicare and Medicaid, respectively.

On the other hand, MU also requires 10% of patients viewing, downloading or transmitting their electronic health information, with over 40% of all imaging scans to be made accessible via certified EHR technology.

The above requirements are hardly a testimonial to efficiency. One study on MU published by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) in 2012 found that medical residents reported having to spend the bulk of their time updating charts and documentation, and that EHR adoption correlated directly to reduced time for direct patient care.

Radiology strives to remain at technology cutting edge

This is a profound challenge. Radiology has traditionally been the medical speciality at the cutting edge of technical advancement. It was radiology which first moved away from paper to digital technology. As a result, radiologists and industry are currently seeking to fast track solutions for increasing patient downtime and improving workflow.

Data use

In the first stage, the focus was on enhancing use of available data. Ironically, illustrating the unevenness and asynchronicity in the progress of technology, efforts were concentrated on getting more usable data out of electronic records, which did not always trickle down to radiologists. One reason was the lack of skills. Referring physicians often left responsibility to get approval for imaging to office staff, many of of who lacked the clinical knowledge required to seek such approval.

Automation: From CPOE to CDS

Soon after, the effort shifted to automation, especially in the shape of decision support (and so-called assistant clinical reasoning) tools. Such a process continues, with evolution from static to dynamic, patient-centred tools. A good example of this is the computerized order entry (CPOE) system. In 2012, a study in the ‘Journal of the American College of Radiology’ proved the clinical viability of combining radiology CPOE with imaging decision support, including pathways and algorithms, as well as classification for actionable findings.

One of the longest-used clinical decision support systems is ACR Assist from the American College of Radiology, which is designed to blend in seamlessly with radiology workflow. Clinical data is encoded in vendor-neutral ways, in order to quickly build commercial applications. The ACR has since created guidelines for radiologists and referring physicians to proceed after clinical findings. Others are also stepping in with new initiatives to enhance automation and decision support. Massachusetts General Hospital, for example, has developed Procedure Order Entry (PrOE), a surgical appropriateness system to help identify whether a procedure is necessary, and the implications of this for radiology are under active investigation. By utilizing evidence-based guidelines rather than have a less-informed entity authorize diagnostic imaging, CPOE in radiology not only enhances efficiency, but also the quality of care.

IPads and speed

One unexpected finding cited in the 2012 RSNA study on meaningful use was that residents using iPads were able to enter and update data more rapidly. Indeed, a majority of those surveyed found that iPads led to significant increases in work efficiency.

This was an opportune moment, given that a year previously, the US Food and Drug Administration had cleared the first mobile app to allow physicians to make diagnoses using iPads or iPhones.

Currently, radiology imaging applications for mobile platforms allow remote monitoring and control for a PACS administrator. Fuelled by standard tools such as DICOM viewers, these impact directly on quality control, data management and workflow efficiency.

The implications of teleradiology connectivity are especially dramatic in emergency settings. About five years ago, Mayo Clinic physicians deployed smartphones in order to assess their utility in a telemedicine stroke-management network which connected radiologists to neurologists and emergency physicians at a remote facility. The findings were encouraging, with over 90% of agreement on the key radiological findings. In the future, smartphone-based teleradiology systems are likely to become commonplace among first responders.

Image management and automation

Image management is also being used as a means to automate processes. The fast growth of technology has also necessitated unprecedented collaborations between specialists. Oncologists, for example, have been working with radiologists to analyse datasets for tumour detection and monitoring, and some studies report sharp reduction in the time required to study suspicious tissue.

On its part, Massachusetts General has also developed QPID (Queriable Patient Interface Dossier) to integrate electronic records and streamline providers’ abilities to access details in a patient’s medical history.

Other areas for attention include voice-enabled documentation, accompanied by structured reporting and data sets that pre-populate a radiology report. These not only reduce human error when inputting data but also enables radiologists to interpret and diagnose a study when a referring physician is most in need of the information – while meeting a patient.

From automation to deep machine learning

The greatest benefit of automation is to maximize the use of available data. This enhances the ability to provide not just personal but precision medicine, too. When interfaced to an appropriate radiology-focused IT platform, individual radiologists and the broader radiology (as well as clinical) community will be empowered to benefit from feedback loops that reinforce positive lessons, de-emphasize negative ones and continuously build appropriateness and best-practice guidelines. Based on the templated information in a report, colleagues (real and virtual) would be able to rapidly offer second opinions and perspectives on how to best serve a specific patient-case.

Further down the road are deep machine learning tools which will provide sophisticated, structured and in-depth data on a patient, to enable increasingly informed decisions in the context of specific and individual challenges – influenced by factors ranging from pharmacogenomics to disease staging, age and lifestyle. Such knowledge, which would create highly actionable reports, are expected to dramatically impact upon patient outcomes.

Radiology and public perception

It is no secret that professional radiological societies strongly believe there is a need to improve patient (and public) perception of the role played by radiologists in healthcare, and that this necessitates closer contact with patients. Patients after all seldom choose a radiologist. This choice is made by a referring physician or health plan.

Though radiology is essential to patient care, radiological services often seem inconvenient, a threat to privacy, sometimes mysterious and scary. The connect between a radiologist and patient is intermediated by nurses and assistants (e.g. for injecting contrast material or preparing them for the imaging procedure), or by technologists seen as managers of machines. Various studies have shown that radiologists are not always present during performance of a study and seldom introduce themselves to a patient.

As a result, patients increasingly consider radiologists to be supervisors of a technological process. The clinician requesting the examination and receiving the radiology report is considered to be the one interpreting the study and making the decision.

Patient at the core

To sum up, the core value proposition in transforming and keeping radiology up to date involves the patient. Although the growing digitization of healthcare pushes radiologists away from patients, there is a need to make these interactions more prominent. Some radiologists warn that otherwise, there is a risk of their services becoming commoditized. For such a process, there is clearly a need to draw more patient data into decision-making. One of the most ambitious efforts on this count was launched at the turn of the decade by RSNA, with funding from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. The project, which promotes patient access to self-management tools, is known as Image Share, and consists of a secure network based on open-standards architecture. Images are exchanged between servers at radiology departments and imaging centres via the Cloud. A two-year pilot began in 2011 at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, followed by university hospitals in several states. In 2016, RSNA introduced a validation programme for the project, to test vendor system compliance with standards for exchange of medical images. To date, results have been satisfying.

Although initiatives like this will continue to grow in importance, they are unlikely to do more than enhance the efficiency of radiologists – and their professional judgement – in improving patient care.